Aerial Straps Review Pt. 3 – Caffeinated Acrobat Straps

Caffeinated Acrobat straps are made by a straps artist with safety, grip, and comfort as the priorities, and it shows. I trust them quite a lot, find them versatile, and still quite comfy (but not as comfy as some of the microsuede/velvet makes).

Total scores

Price: 7.5

Comfort: 7.5-8

Safety: 9.5

Versatility: 8.5-9.5

Customer Service: 9.5

Cleanability: 9

Aesthetics: 7.5

TLDR: Overall, these are good straps that I’d recommend for higher level straps artists putting a lot of use on their straps who want to have confidence in the quality of the straps they are using for dynamic skills, drops, etc.

Okay, now let’s get into the details

Price: 7.5 – at $311 USD plus shipping these are in the upper-middle of range of prices so a bit pricier, BUT you’re getting straps that have a shelf life of 3 years compared to most other straps shelf lives of 2 years. It’s on par with other Australian straps producers like Habitat Circus, but what seems to be higher quality stitching and materials used.

Comfort: 7.5-8 these are comfier than Alexander straps (covering those soon) but less soft/comfy than Habitat or Lyon (in terms of the cover/sheath). The straps were built by someone with slightly larger hands and so the strap width + keepers are made for a larger hand size. The larger keepers might be an aspect that folks with much smaller hands don’t like as it can be hard to hold it in your hand at the full amount of finger closing grip. For reference, I have somewhat small hands for someone who is 6′ tall.

The width of the straps made them less slicey for rolling/c-shaping/etc, and the diffuse the total pressure on the wrist and carpal tunnel (as opposed to the thinness of Lyon Straps, which gave me finger numbness for the first time in ages).

t

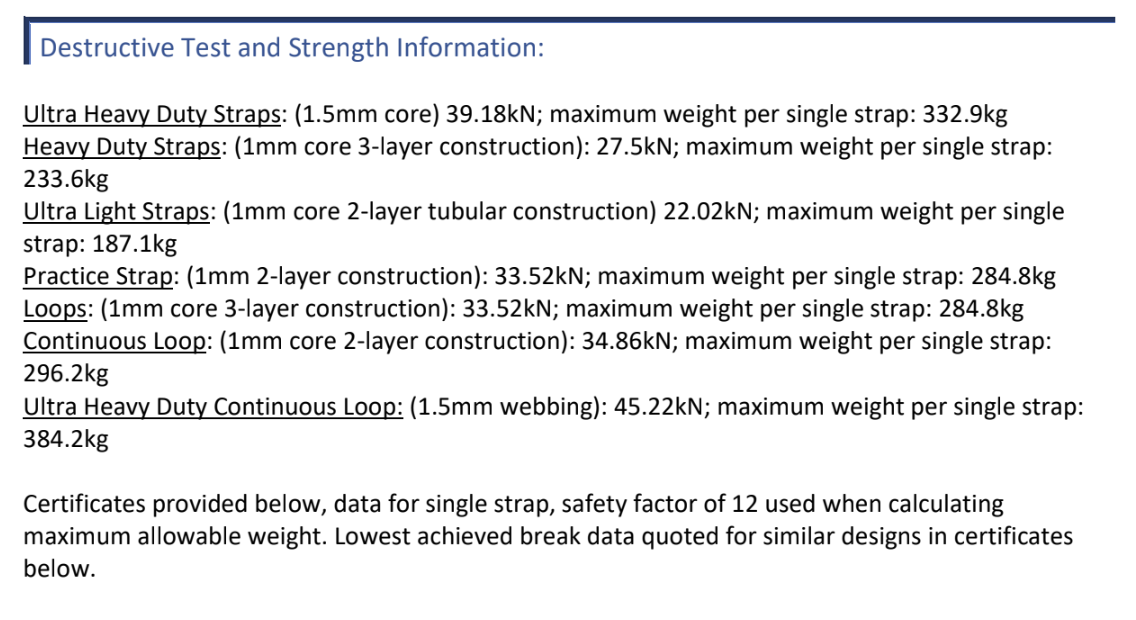

Safety: 9.5 – These straps are made with high quality dyneema stitching, and a Nomex tubular twill webbing outer in black and white (dyable upon request), for superior abrasion resistance, grip, and softness. The core is UHMWPE (ultra high molecular weight polyethylene) core for optimal tensile strength. UHMWPE was selected for its extreme strength, allowing for thinner designs that still exceed the desired strength for a set of aerial straps.

I’d give them a 10, but I just don’t have enough long-term data yet to mark them as perfectly safe all the time. He has break-tested all of the different models below, and look at those numbers!

.Versatility: 8.5-9 – these are a range because it depends on your hand-size and preference for thin/wider straps. That said, I did some pretty high level dynamics and rolling on them, and overall they were pretty versatile. While they’re not a soft as Habitat, they felt pretty good to roll on, and I’d trust them more for dynamics than Habitat. In terms of gripping the straps above the handloops, they’re much easier to grip than something like Lyon or Habitat due to the increased friction and width of the straps.

Customer Service: 9.5 – they’re made by a straps artist with a goal of making straps that are safe, grippable, and comfortable. Tim is invested in making the best product he can, and is open to feedback (and he also acknowledges that there is no one right pair of straps for everyone!).

Cleanability: 9 – Tim recommends handwashing using soap flakes or a similar gentle detergent and air drying for a deep clean, otherwise a small amount of isopropyl alcohol to clean small spots.

Aesthetics: 7.5 – getting a solid dye to stick in the Nomex is tough, but that’s the trade off you get with this level of safety and durability compared to other straps.

Overall, these are good straps that I’d recommend for higher level straps artists putting a lot of use on their straps who want to have confidence in the quality of the straps they are using for dynamic skills, drops, etc.

Aerial Straps Review Series Pt. 2 – Lyons Straps

Straps made by a straps-mom. Lyon Straps are new on the scene, but so far have been slinging straps left and right to folks who last minute need new pairs and are based in the US or CA. Overall, they’re a solid option for pretty comfy straps for nearly all skills.

Total score:

Price: 7.5

Comfort: 8.5

Safety: 8.5

Versatility: 8

Customer Service: 9

Aesthetics: 9

Okay, now let’s get into the nitty gritty!!!!

Price: 7.5 – at $295 including shipping these stack up to be somewhere in the upper-middle of the range of prices, if you’re shipping to the US (then you avoid import taxes and higher fees). Generally, I’ve only seen higher prices so far with Habitat Circus, and with looped straps (because, ya know, more fabric, etc). That said, for suede, microsuede, velvet, you’re almost always looking at the upper end of the price range, and in most cases, I think the extra cost is worth it.

Comfort: 8.5 – they’re honestly very close to Habitat Straps but with smaller keepers/safeties, more cross-stitching, and a feeling of looseness in the cover over the core. The smaller keepers might be an aspect that folks with much smaller hands like, though I had a pal who is a female aerialist try them, and she found the keepers to feel weirdly small as well. For reference, I have small hands for someone who is 6′ tall. The cross-stitching being longer by the handloops is only an issue if you’re flipping and twisting them to make auto-cinching loops, and then you’ve got a larger portion that’s really stiff. The looseness of the cover on the core just felt a bit weird when grabbing it, but is super minor.

That said, like I say in the video, these are some of the comfiest straps out of the box I’ve used so far (Habitat is up there as well), and they really do feel pretty solid for spinning, waist rolling, ankle locks, etc. The keeper size makes them feel a bit weird with more dynamic load.

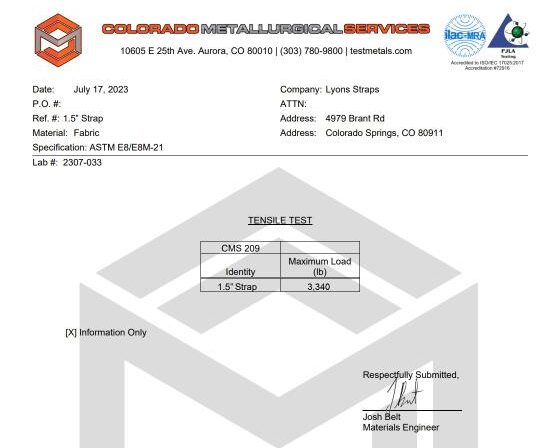

Safety: 8.5 – Straps are made from nylon core, with a polyester suede covering, sewn with a high tensile strength bonded nylon thread. All straps are pulled with weighted tension before leaving their facility (this is something I super appreciate after having a strap fail on me that could have been avoided with weighted tension pulling). The straps are 3rd party load tested as well! The stitching looks pretty solid in most places with only a few loose threads (but truly minimal here). The more slippery the strap, the more I’m stressed about slipping through, but this only matters with super high load dynamics.

The only other reason they’re an 8.5 is that I just don’t have enough longitudinal data to refer back to since they’re new. But I’ve got a good feeling about their straps!

Versatility: 8 – I don’t think I’ll find a pair of straps that will ever be top rated for comfort while being top rated for versatility unless I commit to using rosin or wetting my hands any time I want grab above the handloops of really comfy suede/velvet straps. The area where they lose a bit on versatility is that they’re harder than Habitat Straps to hold above the loop. Otherwise, these straps are great for waist rolling, spinning, and are pretty great for most swinging. The smaller keepers and the more slippery cover make me feel less psychologically comfy with super dynamic movements on straps (big beats, drops, and dislocs) but they’re still good for swings if you pay attention to any loop slipping.

Customer Service: 9 – they’re made by a straps parent, and so it clearly shows that they care about safety and quality. Shipping was fast and flexible, and overall, they were quite responsive. I don’t have lots of data about other experiences with them and they’re relatively new, but fingers crossed it stays that way!

Cleanability: 9 – Cleaning is simple, cold water mild soap, hang, or lay flat to dry.

Aesthetics: 9 – again, I love the color purple. We’ll see if/how it fades.

Overall, these are solid straps that I’d recommend for most skills at a reasonable price point for anyone purchasing in the US/Canada.

Aerial Straps Review Series – Pt. 1

Alright y’all, so I’m starting a new series based on the many questions I get about what straps I use, where to buy them, and the pros and cons of each of the different styles and producers of straps. This was partially prompted by my video of single strap breaking on me while doing beats in front of a bunch of my students.

This list most likely isn’t exhaustive, but I’m reviewing the major producers that I’m aware of being used consistently in our industry and space.

The companies I’ll be reviewing for their 3-meter straps so far are:

Habitat Circus – an Australian company that’s relatively new, but hit the scene for their comfy straps

Alexander Acrobatics – a tried and true German company

The Apparatus Lab – a new producer out of Greece

Les Atelier Forest – a Quebec-based company that’s been around for a quite a while

Circus Concepts – the other Quebec-based company that’s been around for a while

Lyon Straps – a new Colorado, US-based company that’s run by the parent of a straps artist.

I’m going to review them each on price, comfort, safety, versatility, customer service, cleanability (yeah, I made it a word), and aesthetics.

If I’m missing any makers of straps, feel free to write me and recommend I review other straps makers!

Let’s start with Habitat Circus! Here’s the lil’ video, and here’s how they stand out so far:

Price: 6.5

Comfort: 9.5

Safety: 7

Versatility: 7.5

Customer Service: 7

Cleanability: 9

Aesthetics: 9

Price: 6.5 with a price point of $335USD for 3 meter pair including taxes/shipping (but not any import fees – I had to pay around $25CAD to receive them here in MTL). This is definitely a bit on the higher side as pairs of 3 meter straps go. Most straps these days fall into the $200-$300 USD range before rigging (and rigging brings that WAY up)…these are above the general range I’m seeing so yeah, that’s why it’s a low score.

Comfort: 9.5 holy heck, they really are SUPER comfortable on the skin in terms of friction AND they do a solid job not putting too much pressure on any of the nerves (still a potential for nerve pressure with thinner or more sensitive wrists). That said, I did get some numbness and tingling from them, and I haven’t gotten that from my Alexander straps. Overall, they do feel pretty dang nice on the skin.

Safety: 6.5 – on their webpage, they only include the breaking load rating, but there is a QR code (didn’t work for me) on the straps that should contain their load testing certificate done by both Habitat internally and a 3rd party tester. Internal break testing shows a breaking load of 11.1kn. The 3rd party certificate lists that the sewn eye at the end broke at the stitching at 11.3Kn of force. This document has the manufacturing date and the suggested retirement date and time (essentially after 500-1k hours or by 2/25/2026).

On both straps, the stitching is nominally incomplete and asymmetrical, which is another part of why I’m dinging them a bit on safety. Even outside of any actual potential effect on load, it just doesn’t make me feel as comfortable as stitching that looks like it has been conscientiously done – I don’t want something sloppily done when I’m hanging 20′ in the air swinging from one arm. I’ve heard other reports of this being the case for folks with their straps. Dropped stitches, incomplete lines, etc are relatively common with these straps based on the pictures I’ve seen so far so definitely inspect your straps.

The internal load test and date of production info provided by QR code.

Finally, I’ve seen what appears to be the same rigging/swivel plate that they sell also listed on Amazon (by all appearances, but I have no way to know), on both there’s no branding or serial number on the rigging plate. I know I’m not here to review rigging, but just something that might give some folks pause.

Now, I’m pretty sure that not a single producer of straps will get a full 10 out of 10 in the safety category. This is partially due to risk assessment having a level of subjectivity with even professional riggers disagreeing on what is more/less safe, and partially due to me having a bit of inherent distrust after having a strap break on me.

Versatility: 8 – they feel great for swings, spins, and waist rolling (as much as waist rolling feels great)….but they’re quite slippery (at least for my puny weak fingers) so gripping above the loop feels harder than on some other style of straps (that are less comfy on the wrist skin). I could still grip above the handloops, but all in all, it was harder, and I think if I was doing lots of dynamic work above the loops, I might get frustrated.

Customer Service: 6.5 – overall, they were relatively responsive, minus leaving a few of my questions unanswered. They did ask for feedback, which is not a bad sign. That said, I’ve heard from quite a few people (aka enough to include this in my review) but generally, it seems that the customer service is sometimes not great by being slow, and/or non-responsive. That said, small businesses often run into this issue because they don’t have lots of staff so take that with a grain of salt.

Cleanability: 9 they’re anti-bacterial and you can wash them in a cold wash (and air dry them) if they get bloody/sweaty. That’s nice that it’s very clear how you’re allowed to clean them especially if they get high use.

Aesthetics: 9 the dye is gorgeous right now. We’ll see how it holds up/fades, but so far, I’m a big fan of the color.

All in all, these are REALLY comfy, pretty, and easy to clean straps. I’d recommend them to anyone who’s doing lower-load or lower-risk skills who doesn’t mind paying a premium for comfort/aesthetics, AND is comfortable with the dings on safety and potential customer service (though this may change as they grow).

If you’ve got questions/comments/concerns about Habitat straps or other straps from different producers, email me at ko******@***il.com OR DM me on IG @circkoz.

I hope this helps you decide where you buy your straps from!

Language Use, Perfectionism, and Nervous System Regulation – How They Impact Our Training/Performing ft. Janelle of CirquePsych

Alright, y’all, we’ve got a new episode up with @janelledinosaurs AKA @cirque_psych (LSW). In this episode, we covered how the language we use can impact our physiological response in training, the benefits and detriments of perfectionism as it applies to training, and how to regulate our nervous system to support our goals (and just generally had a great time!).

Janelle is a contortionist, aerialist, circus coach, and therapist (LSW). She started @cirque_psych in 2018 in response to seeing a need in the circus community for more transparency and vulnerability around mental health and mental illness. Janelle’s work supports circus folks in improving their relationships with themselves, and uses circus analogies to explore topics in mental health, wellbeing, and social change. Check out her website at https://janelledinosaurs.com/ and the articles that we mention are listed here:

https://flowmovement.net/poleflowblog/2020/06/alettertothepolecommunity

Autoregulation, Minimum Effective Dose, and Oral Contraceptive Use on Maximal Strength Output (ft. Dr. Eric Helms)

Ever been curious about how to assess when to stop training a dynamic aerial skill versus a strength skill? In this episode of CircSci, we explore the way you can use autoregulation and repetitions left in reserve to pick sets/reps and load for differing types of exercise and skills.

Throughout my coaching and academic careers, I’ve always looked up to experts who: were constantly learning, humble, passionate, and admit when a question or idea is beyond their scope of knowledge. Dr. Eric Helms (@helms3mdj) is one of those people. He not only was open to doing an interview, but touched on a NUMBER of different subjects beyond our overall topic of autoregulation in bodyweight strength training, aerial, circus, and gymnastics. Eric is currently a research fellow at the Sports Performance Research Institute New Zealand, author on MASS Research Review, two books, and competes internationally as a powerlifter, strongman, and bodybuilder.

Please enjoy this lengthy podcast episode covering auto-regulation for strength training and skill training, minimum effective dose, and oral contraceptive impact on performance (piggy-backing a bit on the last episode with Dr. Jess Allen). As usual, if you have any questions for me, please comment below or email me at ko******@***il.com

If you’ve got more questions about the newest research in strength training science, check out MASS (Monthly Applications in Strength Sport) Research Review and give Eric a follow @helms3mdj and subscribe to his channels as he puts out incredible content constantly!

Hormonal Cycle Periodization – The Pun Wasn’t Made

Interview with Jess Allen – @awyrol – who is an aerial instructor/performer in Wales, has completed two PhD’s, and has spent the pandemic looking into periodization into relation to hormonal changes because she’s a bit mental (in the best way!).

We cover the effects of hormonal cycles/changes as reported in meta-analyses, anecdotal experience, and ways to periodize or autoregulate your training to adjust for those changes.

Aerial Exercise FOMO – When to Throw a Drill Out?

You’ve probably seen the MULTITUDE of new mobility, proprioceptive, prehab drills, and other exercises being posted on the internet since the start of the pandemic, and you might be thinking;

“Shit, I need to do all of those to make sure my body is properly warmed up, and I’m not missing anything in my conditioning or training!”

Aerial has TON of requirements on the body so it can be easy to feel like we need to do a ton of drills to address those requirements.

You end up with a list 300 exercises long, so you get up at 5am (or stay up until 11:30pm) doing them and you lose out on your sleep, relaxation time, or just find yourself training for way too long (especially if it isn’t your job).

The TLDR is: if you’re spending hours a day training, doing a variety of drills, and aren’t making progress, change how you’re training. If you’re training hours a day, doing drills that have redundant pathways, consider being choosier about the skills/drills you’re training to save yourself time, potentially reduce risk of injury from overtraining, and learn, for yourself, what the minimum amount of time/effort is for you to train a skill and safely progress.

What if there were ways to make progress on certain drills or skills without EVER training them directly? What if the concept of specificity only goes so far for certain things?

For those who are newer to the principles around training for sport, those principles, including specificity are:

- Individual Differences: what works for one person, may not work for another, and vice versa. For example: don’t teach or train a beginner the same as an advanced athlete.

- Overload: to improve over time, increase the stress or load the muscles (and to some extent tendons, ligaments, and bones) are exposed to. In aerial, looking at individual exercises based on the ease of adding or reducing load in them to increase the workload and stimulate for supercompensation.

- Progression: as fitness level improves, training should become more difficult and the workload greater. Over the course of a training program, the workload becomes greater in different metrics like volume, intensity, range of motion (ROM), or total capacity for fatigue.

- Adaptation: ideally, the body adapts to training over time – if it isn’t it is probably time to re-assess training method, program, or factors like sleep, diet, or stress.

- Reversibility: how much time and effort a skill takes to maintain – learning to drive or bike is a low reversibility skill.

- Specificity: training for a particular athletic activity, drill, or skill. This exhibits in circus with the belief that it is only possible to make progress on a skill or drill if you’re doing that exact skill or drill.

- Periodization: systematic and structural variation in training plans or programs over time.

Consider modifying the mentality of required direct specificity to incorporate the idea that you can make progress on a skill without directly training that skill. This is one way to save time and cultivate a mindset in which you can see when one skill or pathway you’re training will build strength, proprioception, et cetera for a host of other skills.

For Example:

Let’s say you want to get hand-assisted single coil roll-ups to back balance (Back C) or beyond to Front C, and also want to build strength in your back flag (also Back C).

In a training session, you could train:

- Progressions for waist roll-ups on rope

- Back flag progressions

- And/or accessory drills to help with shoulder extension and internal rotation, side bending, elbow extension, and hip extension.

This would definitely work, though it might take extra time or require apparatus switching (which isn’t always allowed in today’s COVID world.

Or you could program a cycle (maybe 4 weeks) where you work and focus on:

- Progressions for entering your back flag from skin the cat or from meathook (passing through your Face-down Side-C) to build strength through your shoulder, lateral, and posterior chain.

If you test your side planche or back balance roll-ups at the beginning and end of the cycle, you’ll likely find them either to be the same or improved without any direct work on them. You’d probably also see benefit in your back flag from waist roll progressions that load the shoulder.

Consider the benefits of training a position through a range of motion (ROM), rather than doing static or isometric holds. Besides the fact that this can save you time, it also builds greater awareness of what is firing to maintain a position in the variety of subtle differences within one position and gives greater freedom of movement for aesthetic and skill choice.

Rather than holding an ideal back balance on rope for time, someone would likely gain more control, proprioception, and strength from moving between back balance position variations by rolling up and down the pole (using assistance as needed).

Rating or Categorizing a Drill

There are different categories of exercises that can help you pick which you HAVE to do, which might be useful under the right circumstances, and some that maybe just aren’t worth doing. In all of the examples, the idea is that you are already able to do some form of the mentioned drill safely.

- GREAT (NEED to use) exercises:

- Use full ROM – and build strength and control in the full ROM.

- Progressive – has clear progressions from beginner to pro

- Build towards a multitude of pathways

- Leads to gains in areas specific and nonspecific to the exercise

- Build strength in the stabilizing muscles of the joint

Example: A GREAT exercise would be back flag rocks, which build strength, control, and endurance for back flag, towards vertical flag, and a variety of entrances and exits.

- GOOD exercises (use sometimes)

- Are supplemental drills/exercises to use if you know you’ve got a certain weakness in a pathway

- Have utility in more than a few instances

- Help overcome a plateau when you are having trouble progressing beyond a certain amount of strength/ROM in a movement

- Safely allows for loading more weight/resistance/intensity in non-risky joint positions

Example: A good exercise would be something like pull-ups, a non-specific strength drill that builds strength and control through a large ROM, can help with eccentric control in moving to a straight arm hang, and benefits inversions and front levers.

- MEH exercises – those hardly worth doing (use minimally or not at all[PS5] )

- Hyper-specific to your goal

- May be a waste of time – is there an exercise you’re already doing that uses the same muscles in the same orientation but also provides broader benefits?

- Builds up unnecessary fatigue in your workout

- Takes away from the time spent on GREAT or GOOD exercises

- Only useful in few specific instances

Example: hollow body rocks and holds. Unless someone has a really hard time understanding the front dish/hollow/sweep position in a front beat, there are so many tools that build core strength and positional awareness (specific to beats/swinging) that aren’t just static holds or rocks. Hollow body holds also can end up with people using their diaphragm as a core muscle, which can lead to some really strange breathing mechanics.

Here are a few examples of drills that I think can be left out of (most) training sessions for (most) people as they progress. Even if you disagree with the below, hopefully you start analyzing what you’re doing in your training and if it is actually serving your goals.

Example 1: Straddle Meathook Windshield Wipers

Good: this exercise has some utility early on in teaching the pathway and the lifted hip position in meathooks. Builds some awareness of leg pathway for some transitions.

Bad: only builds strength in the isometric shoulder closed position, rather than lifting or lowering from meathook or nutcracker. Some progressions are there, but often unused.

Once someone can successfully hold a meathook, drop their hips, and pull back to a lifted meathook, there isn’t a compelling reason to spend a bunch of time training straddle meathook windshield wipers. At that point, move on to other drills that build more strength, more dynamic proprioception, and use your time more efficiently.

Similarly, 1-arm meathook to 1-arm nutcracker and back by lifting the opposite leg (doing a 1-arm windshield wiper) only builds isometric shoulder strength in a single position.

What might be better: there are plenty of inversion progressions that build towards 1-arm isometric, eccentric, and concentric shoulder strength while training core and lower body transitional/positional awareness and strength.

Someone working 1-arm inversion progressions is likely going to make gains in 1-arm windshield wipers without ever touching them, while someone just working 1-arm windshield wipers will find likely find their 1-arm inversions stagnating.

Example 2: Inverted Pencil Shrugs and Inverted Internal and External Rotation

Good: this exercise can be useful with the right cueing, especially for beginners who aren’t stable upside down yet. It can help people get a sense of internal and external (IR/ER) shoulder rotation with their arms by their sides. Holding it for time could be argued as a way to train grip endurance.

Bad: understanding shoulder rotation doesn’t always carry over between right-side up and upside-down and arms overhead versus arms at your sides. Someone good at internal rotation and external rotation in pencil may not have ANY idea of how to make ER happen with their arms overhead. I have seen it end up getting people over-engaging their upper traps. Doesn’t have lots of carry over to other pathways or skills. There are drills that teach shoulder rotation in a greater ROM moving between bent and straight arms for shoulder extension, flexion, and at neutral.

What might be better: full range of motion overhead bent to straight arm pressing drills using banded resistance to cue external rotation. As an added bonus, you could add weight and control your arm moving into flexion (or opening your shoulders). You could then rotate to internal rotation and extension a la back flag or skin the cat.

Example 3: Back Lever Froggy/Straddle Extends

Holding a tuck back lever (like a shallow skin the cat), and extending the legs out into a straddle or froggy straddle in little tempos.

Good: builds time under tension for isometric shoulder strength in an extended position resisting gravity.

Bad: the primary factors in a full, legs together back lever are shoulder strength (pressing out of shoulder extension) and posterior chain activation (getting the glutes to lift the legs up and trunk to hold pelvis up). It is another example of an isometric hold in the shoulders with a leg position, the froggy straddle or straddle, that doesn’t build strength in the hips in a way that translates to a full, legs together back lever (even one leg extended and one leg tucked would be better).

What might be better: consider drills that progressively (perhaps towards 1-arm) builds strength in the full ROM from a deep skin the cat or german hang all the way up to pencil and/or an exercise that builds the trunk and lower body posterior chain strength needed for holding a full back lever.

To illustrate, I have a student who made static back lever gains just from doing shoulder directed c-shaping exercises in the All Apparatus C-shaping Manual without her doing any direct back lever work.

There are some skills that need direct work to make progress on, but before assuming a skill, strength, or drill needs direct work, critically assess if there are ways to make gains on it while making gains on another skill at the same time. Most beat pathways tend to need direct work to be smooth and effortless, but successfully beating to an end position, like side planche or Back C, requires that the end position, your side planche is solid. The first time I tried split grip beat to side planche, I’d never done a split grip beat, but had enough experience in my back flag that it worked first try (and that’s not because I have amazing beats like Alex Allan…I don’t).

All of examples above are exercises that you could use if you had a REALLY compelling reason (whether it is for warm-up, a workout finisher for volume-based overload, or something else…like they’re just for fun!) for them. The goal is to illustrate that there is a hierarchy among drill utility that can frame how to choose the primary exercises used in any given training session. As you learn more about your own body, what it needs, and works for it, start to be choosier about your drills, and even make your own drill hierarchy.

If you can’t come up with a clear reason why, reassess that drill’s place in your workout and your drill hierarchy. If you’re spending 5 hours training 300 different drills that have similar movement pathways or muscle activation, consider instead looking for a drill or two that effectively and efficiently targets the desired outcome.

Check out this article on periodization and reversibility to learn more about how to program your own training in the long run, and check out this article on autoregulation to learn strategies for picking rep ranges in individual workouts. Please email me at ko******@***il.com with any comments or questions. If you’re looking for help with your own training, building your own training program, or for someone to build your own training plan, email or fill out this intake form.

Thanks to Trisha (@theflyingchemist) and Ariane (@itsarianelagulli) for reviewing!

Are common Aerial Strength Training models wrong? Considering Autoregulation in Circus

This article was inspired by research synthesized by the amazing folks (Greg Nuchols and Eric Helms) at MASS (where they review loads of research on lifting) with a focus on application to aerial and circus training.

Traditional circus training is a world unto its own. Body positions, loads, angles, and leverage are unique to many circus disciplines so it’s no surprise that many methods have evolved from generational knowledge. With regards to strength, progressions can often be passed down from coach to student, with little deviation from the program. With regards to circus families, this makes sense, as techniques that work for the older generation are likely to work for the younger, especially if they begin circus training early. However, for those who are introduced to circus later in life, and for those with different backgrounds, it may be helpful to reexamine these methods.

The accepted ideas for much of circus strength training is to work to failure as well as the idea of always putting the work in (grind grind grind). These ideas can be dangerous considering that many artists practice in the air or are practicing incredibly dynamic movements on the ground. Grinding away when muscles are fatigued isn’t only potentially increasing injury (chronic or acute) risk, but also can diminish gains. Therefore, it may be better to think of circus strength training with regards to perceived exertion.

According to Greg Nichols, author of Stronger by Science, “Intensity is the primary driver of strength gains, and [I think that] staying further from failure during training helps ensure that subsequent workouts are also high quality.” This study1 by Schoenfield et al (2017) on powerlifting showed gains among trained lifters in 1RM (1 rep max) strength were greater in higher load (>60% 1RM) with lower rep training, rather than low load (<60% 1RM) and higher reps. This powerlifting study indicates that, indeed, intensity of a workout leads to greater gains. Reading this, we might think that training at or above 60% of our 1RM with fewer reps is the way to train.

Hypertrophy is often defined as an increase in muscle size (thickness/diameter), which is sometimes conflated as being directly correlated to increased maximal strength output, but that is not the case. In general, hypertrophy isn’t going to have a huge relationship to circus and aerial skill success.

Based on research1, 2, 3, the goal in training would be then be to maximize training intensity, but stay away from training to failure. Again, our goal is to maximize gains while limiting injury risks. Evidence shows2 (Davies et al, 2016) that there is no difference between failure and non-failure training in terms of maximal strength gains. However, because “failure” training has some other impacts (like increased muscle damage, decreased motor learning, and increased recovery time – thanks for the update, Eric Helms), failure training for a lot of circus skills work may not be the way to go. That said, “failure training” can have benefits for increasing strength endurance (like holding a reverse meathook), though as always, here’s a study which shows that failure training may not be necessary for increasing endurance if maximal training volume and intensity are equalized.

What about the research that indicates performing a strength training exercise to failure leads to greater gains than a lower intensity?

Research3 by Nobrega and Libardi (2016) has suggested that “failure training” recruits more motor unit activity (the primary contractile unit of muscles), and with more muscle fibers working there should be more muscle adaptation. However, the trick with all of this research is that strength training studies are usually over a short time-frame with a specific type of participant (trained/untrained, adult/youth, et cetera) without always looking at longitudinal rates of adverse events (injuries) in response to type of training analyzed.

Because circus has a high risk for injury, recruiting more muscle fibers (via training to failure) may not be optimal for all trainees in the long run. For example, training back flags (which takes just about our entire posterior chain) until you can no longer hold them can lead to compensatory patterns (in an already risky position) over time or acute injury.

Training to failure (either through high load or through high reps) may lead to greater gains. But our gains slow down if we get injured.

Some of the meta-analyses (or studies within them) are looking at untrained subjects when showing the lack of effect for training to failure, and trained subjects when looking at the effect of training to failure. Very few of these studies look at long term changes (a year or more of training) as well as the longitudinal health effects of training to fatigue.

In one 10-week study4 (Martorelli et al, 2017) of active women under 18, resistance training their biceps to failure did not lead to additional gains in max strength, endurance, or muscle size (of the biceps), with impaired force production at faster muscle velocities (for those training to failure). Force production (impaired or improved) at faster velocities has relevance to aerial skills and strength.Though this isn’t studying aerialists, we can extrapolate that perhaps for our younger students, training to failure isn’t necessarily going to lead to better outcomes.

All this to say, there are arguments for training high intensity for time or load stopping training pre-failure as well as training to failure, and even training at a lower loads (to reduce injury risk). A number of studies indicate relatively similar levels of endurance gained when training high intensity or low intensity, while others reinforce specificity (for example, endurance-based strength training leads to greater endurance, rather than gains in maximal strength).

Keep in mind that in general super beginners will overall benefit from high volume work to build capacity. Intermediate level aerialists will probably benefit from a number of sensible protocols, and only at the highest levels is precision in programming necessary to see increased gains.

The above discussion on different types of training protocols leads to two important concepts: individuality and auto-regulation.

Individuality is the idea that what works well for your average person in a program, may absolutely 100% not work for a specific person. Beaver et al. did a rad study5 of TRAINED lifters (rather than untrained athletes) trying 4 different training programs/workout protocols, and then testing how much testosterone was produced in their saliva as a response to each protocol (where Tmax indicates higher levels versus Tmin indicates lower levels). The study then matched each participant with their best/worst protocols (based on Tmax/Tmin). These were the 4 different protocols:

1. 3 sets of 5 reps at 85% 1RM with 3 minutes of rest between sets

2. 4 sets of 10 reps at 70% 1RM with 2 minutes of rest between sets

3. 5 sets of 15 reps at 55% of 1RM with 1 minute of rest between sets

4. 4 sets of 5 reps at 40% of 1RM with 3 minutes of rest between sets

The study either put people in a workout group that generated their highest testosterone response or in a workout group that generated their lowest response. The study matched half the participants with the protocol that produced the highest testosterone response and half the participants with the protocol that produced the lowest T-response, and had them use their respective workout protocol for 3 weeks. They retested 1RM (1-rep maxes) at the end of each 3 week block (as well as whether their acute testosterone responses changed), and then they switched protocols and groups (now half starting with the worst, and half starting with their best).

Which protocol do you think will have the most success?

This is a trick question. Different protocols had different success depending on the person. There was an average (group) increase (around 7% over just 3 weeks!) in strength for those using their Tmax exercise protocol, as well as an individual increases. Nearly all participants saw no gains or decreased strength when using their respective individual Tmin exercise protocols. This highlights individuality among trained athletes – what works best for me, might not work best for you and vice versa.

Most lifters in the study had their best gains in strength (and relative T-response) at 4 sets x 10 reps at 70% of their 1RM, but 2 participants saw strength increases at 4 sets x 5 reps at 40% of their 1RM (and got weaker/no improvement using the protocol above that worked for most other lifters). All this to say: what works really well for most lifters (and we’re extrapolating to aerial strength training) will probably not work well for everyone. While this was a lifting study, the results could definitely translate to circus training.

Remember that each participant was doing a DIFFERENT protocol based on their best/worst acute testosterone response. Don’t get hung up on salivary testosterone measurements as crucial to building a workout plan, but rather (especially if you’re a coach) internalize that there are huge individual differences in terms of response to the same exercise protocol, and what works for one student (or even what works for you) may not be effective for ALL students.

There may be temptation to think, “I must be that unique person who makes more strength gains with a light workout protocol” (or vice versa – the person who has to work REALLY hard to see gains). If you’re a coach, start with what you know works best for MOST people, and then adjust when you have a student who is putting in the work, and isn’t making gains or is even getting weaker. Don’t fall prey to the idea that they are lazy or unmotivated and just need to workout harder, do more reps, or train more frequently – though sometimes that may actually be the case.

What about the thing related to individuality? Here it is – autoregulation!

Autoregulation is the idea of basing our training intensity/load/volume each day based on the person and their physical and emotional state, or individuality (occasionally using metrics like rate of perceived exertion of repetitions in reserve or velocity). In other words, it says that training can and indeed should be customized to daily feedback cues.

Though this has been explored in weightlifting, again, I believe the circus world could benefit from familiarity with it. Just like in any exercise field, some of the notions around strength training in our industry are outdated, are injuring people, or are keeping them from making gains.

This includes the individual’s response to aerial/strength training and other external stimuli like nutrition, sleep, mood, hydration, training volume, hormone cycle, and general socio-emotional/economic stressors.

Just a quick note: the research around hormone cycles impacting training differs from anecdotal experience that I’ve gathered from high level aerialists – again highlighting the potential for individual variability as well as the impact of beliefs/expectations on strength output.

Autoregulation can be a tool to empower aerialists and circus artists (or their coaches) to modify their training based on the above; however, critics of autoregulation, perhaps rightfully, believe that a lot of people don’t know how to (accurately) listen to their bodies due to poorly anchored set points, social pressure, et cetera. Thus, there is the risk that poor autoregulation will lead to people to training TOO hard when they shouldn’t or not training hard enough when they should – rather than using objectively pre-determined metrics like sets/reps and percentage of 1RM (something potentially harder to measure in body-weight training).

In circus, we especially know that some of us LOVE to go hard (and we feel most productive when we’re out of breath, sore, bruised, et cetera), though on the flip side, we also may have that student who will take every opportunity to do as little as possible (and then maybe sometimes complains about never making progress). In a lot of cases, people who haven’t been life-long athletes don’t do a great job of “training by feel”. Life-long athletes may not do a great job of it either considering our brains aren’t always the best at self-assessment.

Luckily, auto-regulation is not solely subjective training by feel in an effort to respect individuality. Instead, it uses evidence-based subjective questionnaires (like those looked at in this review6 by Saw et al., 2016) and other metrics (like the “repetitions left in reserve” metric designed by Mike Tuchscherer discussed shortly).

The questionnaires used are more consistently accurate in monitoring things like risk for overtraining and overall athlete well-being. Biometric measuring, like using blood markers has been shown (see the meta-analysis) to be less consistent. Heart rate variability assessments, which have been touted by some as THE useful measure for self-assessment and autoregulation, only have limited correlation with overtraining, fatigue, and overall mood compared to tested questionnaires and some other metrics.

*At a week long straps retreat, a few of the students had HRV watches, and those numbers did not always match up to how they felt on day 3 of the retreat just before the rest day. HRV said they were golden, but they were fatigued af. That said, the use of an HRV watch can help someone, who may not be great just yet at listening to their body when they train, get a sense of how their body is doing. They can match their numbers with their subjective feeling – when the numbers and feeling match, start to go by subjective feeling since we know that valid subjective assessment tends to be associated with more markers of well-being. This can help people prevent injury and learn to listen to how for much they should train, rather than grinding out reps until they get to the end of their workout.*

The subjective self-report measures in the study above not-withstanding, for autoregulation, the commonly used methods for determining intensity/load of a workout (outside of HRV assessments) are:

- RPE (rate of perceived exertion) – using a scale of how HARD something is.

- Velocity of the lift (higher velocity would mean you can increase the weight). This would be like how fast you could do a pushup. If you can explode up from the ground quickly, you could make the pushup harder (which would likely mean you aren’t able to explode up as quickly).

- RPE (repetitions left in reserve)7 based on the number of repetitions you believe you could perform before reaching failure within a set. This method is highlighted by Helms et al. 2016, and I first learned of it from this article written by Eric Helms.

RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) based on Repetitions in Reserve

Let’s look at RPE based on the number of repetitions left before failure or RPE of reps in reserve7 because in circus/aerial, like lifting, the risk of injury is not worth the potential gains of a few extra reps closer to failure when you’re hanging from one arm.

The general idea is that it is a scale of 1-10, with 1-4 = “very light to light effort” and you could 6 or more repetitions up to 10 = “could not do more reps or load.” I’d argue our goal is to work in the 7-8 range (assuming equivalency of the 70-80% 1RM). The 7-8 RPE (based on reps in reserve) range would mean you believe you could do 3 or 2 more repetitions at the same load.

A student is working on 1-arm inversions, got good sleep, have been eating well, have low/no stressors, and are feeling well recovered, et cetera), then they would do whichever level of bodyweight aerial progression they can stopping once they perceive they can only do 2-3 more full ROM repetitions of that progression. Since they slept well and feel great, let’s say their max that day is around 6 arm and a half lifts to nutcracker, so they stop before failure at around 3, maybe 4 reps.

The next time they work inversions, they feel like junk, but still aim to hit a 6-8 on the scale (in terms of perceived amount of reps until failure). They feel like junk and think they can only do 4 arm and a half lifts to nutcracker so they stop each set at around 2 reps. This may be significantly lower than their max on a good day, but ideally it keeps them from overtraining or risking acute injury due to trying to hit a training load that their body isn’t ready for that day.

You might be wondering how to apply this to aerial training. Based on everything discussed above, consider trying higher load (using different bodyweight progressions depending on your level) aerial strength training, aiming for 3-4 sets of a rep amount stopping 2-3 more repetitions before failure per set. That keeps the relative intensity safe, but high. In other words, the training should be intense, using as much load as the body can handle for 6-8 reps, but should also stop a few reps well before failure.

Now granted, if doing 4 sets of 70% of your 1RM or of a 7 on the scale (2-3 reps left before failure) of your RPE (rate of perceived exertion based on reps prior to failure) without progress or gains, you can always change it. Just remember, it can be easier to ramp things up slowly (or start at a lower intensity) especially to find out if you’re one of those aerialists that makes gains at 4 sets of 40% of their 1RM than it is to go hard, get injured, and have to recover from injury.

Training at a 7 on the scale of RPE, based on repetitions left in the tank, may reduce injury risk, place yourself in a training protocol that works for most people for strength (and other) gains, and give you the flexibility to adjust your plan based on your life, body, and recovery. That said, there many training protocols that will work for most people, especially those who aren’t close to their maximum potential.

This is not to say that if the conventional ideas and protocols around training load/volume relationships and specificity are working for you (they’re much easier to understand for your average athlete: “I do 3 sets of 5 leg raises”) you should throw them out. But if you’re not making progress, consider looking into making these (or other) adjustments. When training and choosing how to train, keep in mind that your primary goals are to stay injury free, have fun, and make progress (in different levels of priority for different people). Worrying about how to make the MOST optimal progress is almost not worth the mental effort unless you’re plateauing or are a professional athlete who gets paid to train.

If you’re curious to learn more about customized program creation, private lessons or training, and auto-regulation, feel free to stay tuned on my website (and IG) for more discussions around the science of training! If you’re looking for more informative and enjoyable writing around the science of training, check out Stronger by Science and the MASS research review.

Thanks to Max March-Steinman, Sadie Brown, and Emma Foster for editing and reviewing my ramblings for readability.

Quick references, but there are way more out there!

1 – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

2- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26666744/

3- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

4- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5505097/

5- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4789708/

Periodization in Circus Training (And a Readiness to Train assessment tool) – OR How to Make Gains and Not Waste Your Time

Variability, Training Buckets, Reversibility, and Skill Maintenance

Feeling like you can’t keep up with all the skills you *need* to work on? Some weeks you succeed more at that one skill than you expected and then you regress (or feel like where did that skill go)? Not sure how to structure your training to make efficient gains?

Some conceptual and practical answers to the above questions come in the form of concepts like variability (which sometimes is looked at through the lens of periodization), training buckets, and reversibility. WHAT THE HECK DO THESE ALL MEAN??!!?

- Variability seems like a pretty obvious concept from a circus training perspective, right? Like train different stuff and don’t beat a dead horse training one skill over and over and over.

- Periodization is defined in different ways in contemporary sport/strength training research but generally means “ideal training structures with set time frames and progression schemes with fitness attributes being developed in sequential hierarchy” or generally put, creation of a mindful training program. Periodization models induce structured variability though research is inconclusive as to which, if any, periodization model is best. There has not yet been much research on periodization in circus. Current research around variability and periodization is primarily looking at strength training – so for us aerialists, extrapolation of the research would be geared towards aerial strength skills like inversions and other movements that require more strength (active flexibility and gross muscular output) to execute rather than creative movements or dynamic skills (those will be touched on later). Similarly, building cardiovascular and muscular endurance to run an act falls into the strength training category. Building endurance for an act still falls into strength related periodization (cardiovascular strength – our heart is a muscle!) and muscular endurance (we still want to be able to use our grip strength at the end of an act). In general, periodization programs are designed to prevent overtraining, undertraining, and plateauing (though in circus, typically we see more examples of overtraining and plateauing, than under-training).

Periodization for Skill Maintenance Versus for Strength Building

Periodization is becoming more known in aerial and circus, with certain coaches at least mentioning it within the creation of their training programs. When I’m coaching or building a program for someone, I use periodization and skill buckets (more to come later) when working with long-time students to help them meet their goals by rotating through skill and strength groups. Since aerial and acrobatic skills rely heavily on strength fundamentals, this is great because it encourages less thoughtless structuring of how to organize training programs and individual training sessions.

Sometimes when I ask someone what they training with the goal of getting a movement or skill, they just tell me they are trying the skill every day with a random rest day thrown in. This scattershot-do-everything-often-approach isn’t really the best method for efficiently and safely learning or mastering a skill.

But there is a difference in how one might periodize for strength training versus skills development and maintenance. Periodization for strength should involve regular deloads (of a lighter week of movement relative to the normal training demands) the strength exercises and strength skills one is training for, while skill related periodization (true skills, rather than strength skills) can be approached differently.

Why do we care about variability in strength training for circus and aerial?

What we do know is that “variation is a critical aspect of effective training” and that high levels of “training monotony –… lack of variation– leads to increased evidence of overtraining syndromes, poor performance, and frequency of banal infections,” in other words you and your training will suffer if you are doing too much of the same (Kiely, 2012). However, too much variability can be a problem too – “if a performer’s adaptive energy is too thinly dispersed among training targets” then likely we will see slower or non-existent gains. Training FOMO (drill and exercise FOMO is the next article coming up!) is a thing – yes, I get it, being determined and hard working and training all the things can feel productive, but sometimes that ends up with the training in general suffering. Picking a focus as a top priority for each training session can help with that.

So how do we structure our aerial strength training in such a way to balance variability to reduce overtraining risks with our desire to make rapid gains?

Finding a balance between variability and focused training may be an answer here. What helps me, and might help you, to do this is returning back to the concept of periodization (or in this instance, really just a training structure of progressions within a set time frame – weeks, not an hour of training) in conjunction with putting the movements I am training into different strength “buckets” – a bucket being functionally defined as all strength skills that involve hip extension, or all C-shaping skills (for example, waist roll-ups on rope), or all pushing skills, like handstands (regardless of apparatus). Your buckets can be made up of whatever distinct movement groupings that make sense for you and what you train.

Up until now we’ve been looking at this through the lens of strength training, but much of aerial and circus includes skills that require fundamental strength AND varying degrees of neuromuscular control and coordination. Here are some useful types of buckets below that one could use to categorize aerial strength skills:

- Pushing (bucket A) versus pulling (bucket B) skills (planks, handstands, the arm supporting your body in a back balance versus hanging leg raises, inversions, pull-ups, et cetera.)

- Anterior chain (bucket A) – so skills that primarily use the muscles in the front of your body versus posterior chain (bucket B) – your back, glutes, et cetera.

- C-shaping skills (bucket A) versus movements that are unidirectional/uniplanar (bucket B) – waist roll-ups versus wheel downs.

- Static strength skills – static switches from meathook to flag and press to scorpion versus dynamic skills – flare to flag or beat to scorpion).

Regardless of exactly which buckets you use, within each bucket of related skills, it helps to then mentally organize skills in order of those with highest reversibility (see below) to lowest reversibility for you (or similarly, difficulty if you are still in the process of learning or acquiring the skill).

Reversibility is the idea that skills which require more constant rehearsal and practice have a higher reversibility. Think of those frustrating skills which degrade or quickly become hard again (high reversibility) versus skills that once you acquire them, you can practice them once a month (or at some low frequency) and they still work (low reversibility).

Skills (and whole skill buckets) may shift in levels of reversibility during your time as an athlete/aerialist, but keeping track of skill and bucket reversibility is worthwhile. For example, complex dynamic skills (so that skill bucket) and within that bucket, top switches (also known as tic/tocs)have generally been high reversibility and difficult for me. I can then use that knowledge to prioritize what skills I put into my training program with a higher frequency. I train top switches often, while very rarely do I train roll-ups or flares to flag.

If you aren’t sure about the reversibility of a skill, usually a good subjective metric is if you can do the skill 3-10 times in a row without fail (depending on if it is a strength skill or coordination skill), the skill likely has low reversibility. If it starts to feel hard or imprecise in the 1-3 rep range, practicing that skill more regularly would be worthwhile.

Keep in mind that strength gains are non-linear and that lower variability training with the goal to acquire a skill quickly can lead to overtraining – so while it is frustrating when a skill or strength that was improving or working well doesn’t work, it also provides information (though in some cases too late) on when to definitely add variability and rest in. What can be helpful is making note of how frequently you’ve trained X skill versus resting versus factors that might reduce strength or induce central nervous system fatigue.

With that in mind, intentionally building in some variability in advance, potentially by planning practice/training sessions with those lower reversibility skills or skills in another bucket is useful in allowing you to focus on certain skills or buckets for a period of time (let’s say 4-6 weeks). This process allows you to balance skill maintenance with training variability and skill acquisition.

So laid out fully you can start by:

- Making buckets of skills that you care about learning and/or maintaining.

- Order them in terms of difficulty of them for use in learning, or level of reversibility in maintaining.

- Pick those with high difficulty and reversibility in different buckets to work in a structured fashion for a set period of time (different buckets each day you train – let’s say you train MWF – for example, you could practice high difficulty/reversibility pushing skills on Monday, hanging skills on Wednesday, and C-shaping skills on Friday). Within those training sessions, put the skills you want/are hardest closer to the beginning of your training session. This will be dependent on what your training schedule is like.

- Add in a regularly scheduled day for rehearsal of lower reversibility skills – it may take some time to figure out how frequently some skills need to be rehearsed before they start feeling sloppy, harder, or you lose them again temporarily. No one has time to rehearse every skill all the time (social lives, naps and baths, and planning your retirement are important too!).

- Take a REAL rest week at least every 4-6 weeks if you can – no matter what your inner voices say, if you’re training hard (rather than training chronically) and working efficiently, your body will probably need it.

- If your training is unfocused, inefficient, and too highly variable, you probably won’t be making gains or pushing your body hard enough for a rest week to feel necessary (though you may still be fatigued).CLICK THE LINK BELOW TO TAKE THE ASSESSMENT! Stay tuned for PART 2 – How to Periodize for a Performance/Showcase/Gig

Be negative (eccentrics) for safety!

Eccentrics (Negatives) for Safety/Injury Prevention

One of the litmus tests that I use before sending someone on their merry way to begin dynamic movement in a certain pathway is whether or not they can do the eccentric/negative with control.

For example, if you were to have someone leave a front-balance into a beat on trapeze, a good litmus test would be to see that they’re able to a controlled lower from toes to bar (leg raise) into a hang. This is just an example, but if someone’s legs fall immediately into a long hang from a toes to bar, there’s an increased risk that in leaving the bar from a front balance into a swing, that they’re putting heavier load on their shoulders and hands. Or if someone did a slower lower of toes to bar but their grip seemed to slip, it can be an indicator that leaving the bar with momentum might increase their risk of their grip failing. Or if their shoulder blades under or over-rotate/tip/elevate while doing the slow lower, chances are, under a fast movement the less ideal pathway will occur.

Now, this is just an example, but the same general thought process can be applied to teaching and learning a lot of skills. It is up to you as a coach (or autodidact to think ahead to dynamic skills and movements to break down potential failure points where having increased control through the range of motion can protect your joints/muscles/nerves from suffering undue damage (from either acute injury or from loss of coordinated motion to reduce repetitive strain type movements).

There are definitely ways that this strategy can get tricky to implement, and this is where finding a high level coach can be useful. For example, there are certain movements where giving a watchful eye to someone’s scapular and humeral control during eccentric movements can be useful in noting where the failure points might be for them (as opposed to just watching them move through the pathway with what looks like good form). If someone is doing what looks like a great looking straddle down (slow, controlled, and with good compression), but their humerus is internally rotated, chances are, they may not have adequate control (in the eccentric) in their shoulder complex.

Another benefit of eccentrics is that increased muscle length (as eccentric exercises have been shown to add sarcomeres in series – ie. making the muscles longer) – because we, as movers of our own bodies, want to be strong in as big a range of motion as we can!

I would recommend using eccentrics as a part of your aerial training, both to functionally work on skills that you don’t have the full concentric motion of, and an an injury prevention tool to build control as an exit pathway from static positions, as well as a visible litmus test for injury prevention before practicing a dynamic movement.

If you have any questions on how to use eccentrics as a litmus test for dynamic movement (or on how to use eccentric exercise without as much muscle damage) feel free to PM me (or email me: ko******@***il.com). Please feel free to respond with comments, thoughts, and questions!

Footnote: Eccentrics have been shown to induce higher levels of muscle damage and inflammation over other types of muscle loading (citation) (and increased muscle damage and inflammation has not been shown to lead to increased levels of strength. However, research has also show that after the first session of maximal eccentric training of a muscle that there is a protective effect for future and following bouts of eccentric exercise (sometimes for up to 6 months) so whether or not you believe that the increased muscle damage is good or bad, it is diminished after that first session, and the benefits of eccentrics (for injury prevention) still outweighs this potential negative (the increased muscle damage). So if you’re worried about training eccentrics, there are ways to mitigate the muscle damage, but I’d still recommend them functionally on many levels.

http://www.lookgreatnaked.com/articles/mechanisms_of_muscle_hypertrophy.pdf – THE MECHANISMS OF MUSCLE HYPERTROPHY AND THEIR APPLICATION TO RESISTANCE TRAINING

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4620252/#B14 – Overview:Physiological and Neural Adaptations to Eccentric Exercise: Mechanisms and Considerations for Training

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4760450/ – Muscle damage and inflammation after eccentric exercise: can the repeated bout effect be removed?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23977721 – Eccentric exercise-induced delayed-onset muscle soreness and changes in markers of muscle damage and inflammation.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/838d/7c00cc996c30837c753c3ee9dddd845680d1.pdf – Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans